By ASHLEY GARRETT

Published in Figure/Ground Sept. 5th, 2014.

Joanne Greenbaum is a painter and sculptor living and working in New York City and Berlin, Germany. Born in NYC in 1953, she earned her Bachelors of Arts degree from Bard College in 1975. Her work has been included in many solo and group exhibitions in the United States and abroad. She has been reviewed in The New York Times, Art in America, Artforum, and Hyperallergic. Her awards include the Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Award from the Academy of Arts and Letters in 2014, the Joan Mitchell Foundation Fellowship, the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Pollock Krasner Grant, and the NYFA Fellowship in Painting. She is represented by Rachel Uffner Gallery in New York, greengrassi in London, Shane Campbell Gallery in Chicago, IL, Nicolas Krupp Contemporary Art in Switzerland, Galerie Crone in Berlin, Germany, and Van Horn in Dusseldorf, Germany. She has an upcoming show of new paintings at Galerie Crone in Berlin this November, 2014.

Can you talk a little about your background and where you grew up?

I’m from right outside of New York in Westchester County. I was actually born in New York City and then my parents moved north to the suburbs. I’m from here, I went to school upstate at Bard College, and I’ve always lived in New York. The last five years or so I’ve been living some part of every year in Berlin, which I really like, and I think it just took me a while to figure out that you’re allowed to leave New York. I just never thought I was allowed to leave, and also for many years I had job. But even after that was over in 2001, I’m just kind of a homebody, I kind of stay where I’m put, but I think now I’d just like to go to more different places. So now I spend part of every year away, and it really makes a huge difference in how I feel when I’m back here, and it’s better.

What do you like about Berlin?

It’s quiet, I would say mostly the quietness and the silence, and the slower pace, but yet it’s a city. It’s also green, meaning lots of parks and since I have a dog it’s nice to be able to take him out without a leash everyday and have him run around. I think mostly it’s just the quiet—I mean for me Berlin is a city with a country feel, so it’s almost like the country in the city. There’s plenty to do, I know some people there, yet it has more of a laid-back feel. Plus there’s a lot of great art there.

Is there anything in your experience growing up that comes into your work or affected your development into the artist you are today?

I think I was probably born an artist, because I’ve always felt like one, even though I didn’t necessarily know what that meant. But in terms of psychology, I think it was a place for me to retreat to escape from my surroundings. I mean you don’t know what came first—either your surroundings making you want to escape, or the fact that I was just kind of a quiet girl who wanted to just draw. I don’t really know, but I think that it had something to do with always feeling sort of intruded upon as a kid, and that I have this incredible desire to just retreat into something else, so I think that’s how I developed this habit of drawing a lot. It was a place I could go.

What was your first encounter with painting?

I always did stuff from age five on. My parents sent me to oil painting lessons from a local artist lady in Larchmont who was an oil painter and she did oil painting lessons in groups in her basement. I remember going to that and encountering real oil paint for the first time. I must have been around 10 years old. I went to her for some years and I really liked it, and she was nice, and as somebody who was coming from a family that was very judgmental, and the teacher wasn’t, that allowed me to just do what I wanted to do.

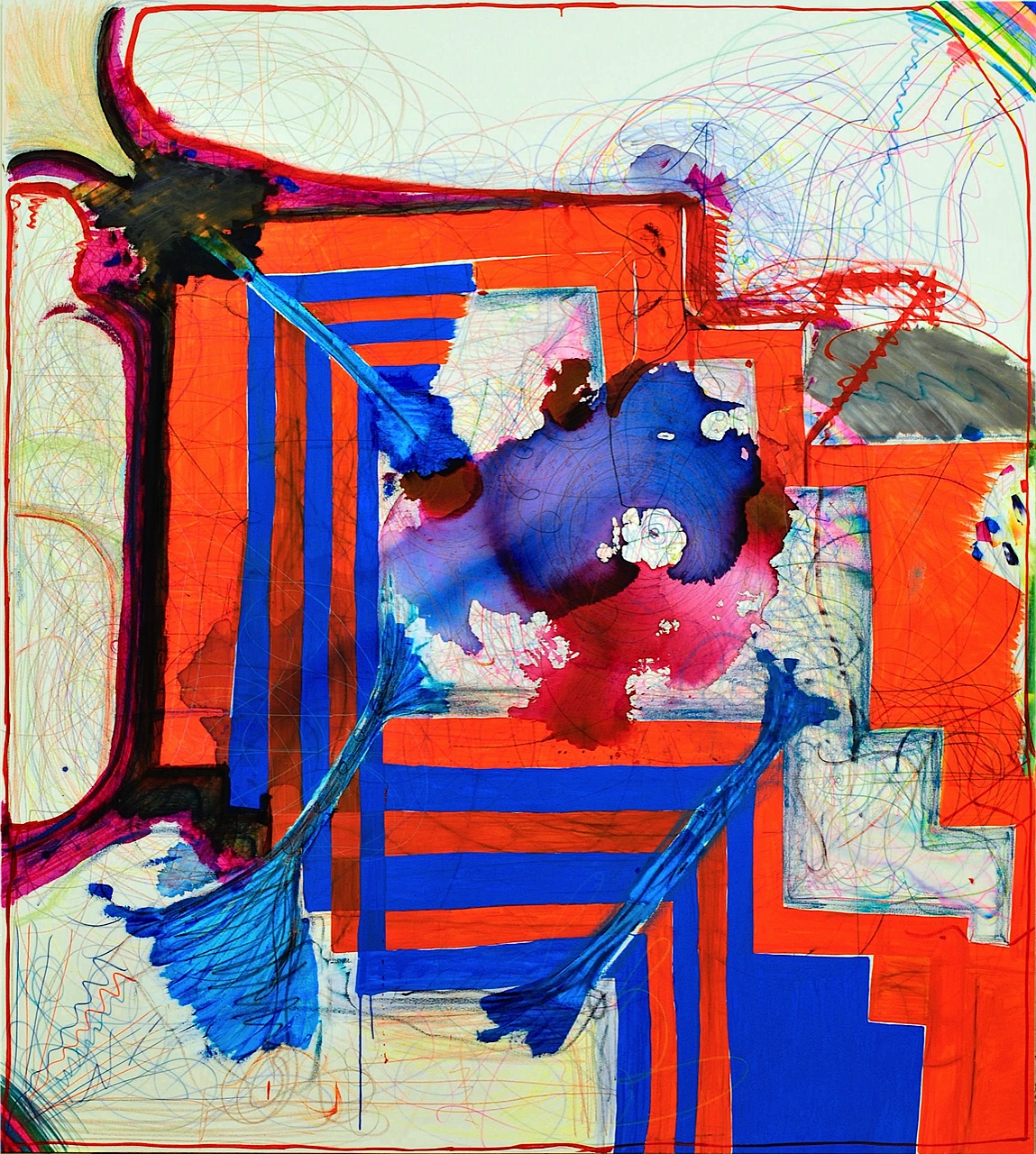

Untitled, 2014, oil on canvas, 90 x 80 in., Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery

I did that too when I was kid, going to lessons—

With the local lady! She was a real artist, and I remember she had this beautiful big old house—

There’s something really nurturing about that, and being in a group where everyone is just learning—

I don’t even remember the other people, I think I was probably the youngest one. But that was probably my first encounter with oil paint.

And you were saying you were always drawing a lot—and it looks like you draw a lot.

Yeah, I always just draw. Even if I’m just watching TV or talking to somebody I’m always drawing.

And it’s interesting how that translates into the painting.

Well, it never used to. That’s relatively new in the last seven or eight years that I incorporated drawing into my work. I always had it separate – there was the painting and there was the drawing. The painting was always more minimal and spare and then there were the drawings, and then I think somehow they merged in the work.

What drove this shift for you?

There was this feeling that I wanted to take the intimacy of drawing, especially the way that I draw. I do a lot of ballpoint pen drawings which are kind of just about my handwriting energy and scribbling, I’m not going to use the word doodle because I really don’t like that word.

They don’t look like doodles to me.

They’re not doodles. Some people say they are, but they’re really not. Taking that intimate type of thing and use it on a big painting it monumentalizes it. You could say these small drawings are not so important because it’s just a notebook drawing let’s say, but then giving that a lot of importance by putting it in a really big painting and trying to translate it in the same way. So in these drawings it’s the hand that’s doing the movement, but in the painting I use my body in the same way to create the same type of energy on the larger scale. It’s not like I take this and blow it up, but I’ll take that same type of energy and use it on a canvas with different materials. But I have been using some drawing materials directly on the canvases as well.

It looks like you’re really getting that, the line is intensely felt on both scales.

Right. I think it just took a while to transfer it, because I used to remember looking at people’s artwork where people drew on the canvas and it always looked funny to me, I can’t really describe it, it just looked fake, or too self conscious. I’m trying to have it be very natural in the process of making the painting, that this is part of that, the drawing is not explain anything, the drawing is not an outline for anything, the drawing is the content, in a way, of the painting.

I know what you mean, I don’t see a lot of painting on this larger scale that has that kind of purposeful drawing in it, searching and full of discovery, free and open. There’s something about that—that the drawing would somehow interfere with the rest of the painting. And I think you’re getting the elements together and truly integrated.

Well, I think the artists I look to the most, or maybe the ones who I relate to the most who achieve that are Basquiat and Twombly. I think those are two examples of artists who used drawing as painting, or painting as drawing. And so when I look at those people, I really understand.

Untitled, 2014, oil, ink, acrylic and flashe marker on canvas, 90 x 80 in., Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery

And with Twombly it’s so spare, but so confident and purposeful, the way it’s done is that you don’t second-guess that the line and the drawing is itself the painting.

Right, it’s just coming from him and you don’t question it. Same with Basquiat as well, who was just an incredible drawer. His thoughts just went right on the canvas, there was no filter going on to make it into “art,” it just came out and that was that. And I think that’s why he’s so good, for him that filter just wasn’t there. I think Twombly is more elegant in a way and more refined. I remember a show years ago he had at the Brooklyn Museum and I remember going to that and it was so weird because it doesn’t happen to me very often—I just burst into tears when I got there. I think right at that time I was starting to do drawing in my work. And then I could see, it was like, Oh my God, this guy did it.

There was no strategy in his work. And I don’t work with any strategy whatsoever. As I’m going I figure it out, there’s no plan going on. And that’s why everything’s different from everything else. I’m not making the same thing in five different colors. I just don’t work like that.

In your Art in America interview you said that you see the forms in the paintings less like maps and more like still life spaces.

Yeah, it’s not necessarily traditional still life space where there’s a vase and things on a table, but because I make sculpture now which is kind of vaguely vase-sized, objects that do go on tables, or bases/pedestals, or the floor. Someone was over today and she asked how I would display sculpture and I told her that at this point I would want one in a vitrine. Like an object in a cabinet of curiosities. So basically I think what I mean by still life space is that since I’ve been making sculpture I think of the forms as three-dimensional things even though maybe to other people they don’t look like that, but to me, this painting that we’re looking at—with the white that was knifed on, to me that’s creating a sculpture. And the red is some sort of shelf or platform for those forms, so I think that I work a lot with a structure that functions as some kind of holder or platform for these other things that I’m putting in the painting, so I think that’s what I mean when I say I’m putting still life space in the paintings.

I don’t see maps. I know people do, they say they see maps in my work, and I never do.

I find that so funny how people get fixated on these really easy readings of people’s work.

A while ago, I think it was when Julie Mehretu got on the scene because her paintings are kind of map-like—I think the word “mapping” became a big buzzword about ten years ago. And so anything abstract was like “oh, you’re mapping the universe, or you’re mapping this, or mapping that.” If I’m mapping anything it’s just my mind, but I still don’t like the word mapping, it’s not something that I think about. People always say that and that they look like subway maps, but no, they don’t. That’s not what these are, and I think they’re getting more and more away from that. I don’t even really know what direction I’m going in because sometimes I want to make more minimal work, but it just doesn’t seem to be going there. Like in this painting that’s unfinished, this morning I thought I was just going to be covering the whole thing in black except for maybe that area in the middle there and just see what happens. So each painting has it’s own life. Mapping is not where I’m at.

Sometimes my small ballpoint drawings are called obsessive too, but it’s just that I like to make them. That doesn’t translate into that I’m obsessed with them, I just like to do it. It has nothing at all to do with obsession.

There’s no subtlety in that, when people get these categories affixed to their work, and it simplifies it and prevents other readings. And so many artists have these collections of buzzwords that people have said or written about them that seems to follow them around. And you’re always having to reopen the conversation.

Well, I think that the art world as it is wants to categorize you into these boxes and I’ve pretty much fought my whole career to not be categorized and not be in a box and not be in a group, and not identify with a school of thought. I just don’t want to do that.

You were saying in your Art in America interview that you’re really attracted to Modernism. Can you talk a little more about that?

First of all I’m not trying to make Modernism. I think there’s been a lot of talk lately about this fake modernism or people quoting modernism in their work, or sort of retro-modernism. I’m not trying to do that. I just think there was so much that happened in classic Modernism that I still find really interesting. I still find Cubism fascinating. Basically it’s the breaking up of space and that’s super interesting to me. That’s not something that ever really went out of style. I’m interested in the breaking up of space, and then I’m also interested in color. I mean I’ve always looked at Matisse’s color, in terms of Modernism; those are sort of my heroes.

Untitled, 2014, oil, ink, and acrylic marker on canvas, 90 x 80 in., Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery

I’m seeing your books and you have a lot of the Modern masters here.

Yeah, I like a lot of good books but I also have a lot of books on contemporary artists. In Berlin I saw the Hilma af Klint show which was amazing. It traveled to a few other European cities, I don’t think it came here. I think the last venue was in Denmark. It was an amazing show and she made those paintings in 1905—before Cubism. She did that before Picasso. It’s kind of mind blowing, even just from a feminist point of view, that she made this incredible monumental revolutionary kind of work and nobody saw it.

There are a lot of these brilliant women artists that are sort of tucked under the legacy of these huge names like Picasso, like Paula Modersohn-Becker is another one. Picasso was looking at her work, actually being influenced by it, and now we’re getting to know the real history a little bit.

Right, and it’s so interesting and also how the canon as defined by the Museum of Modern Art is not necessarily true, even though we were told it was true, and I think it’s really interesting how history is now starting to be rewritten to include people that were very influential or forgotten or ignored. I was having a conversation with a friend the other day, and she was saying how MoMA has a Joe Bradley in the lobby now and a Sue Williams in the lobby too, and that’s pretty cool. If they just had the Joe Bradley that would be wrong because they’re trying to contextualize him into the male canon, but they didn’t –they had a Pat Steir, they had a Sue Williams up, and I think the imbalance is changing but it’s going to be a really slow change. The art world is incredibly sexist at the top levels.

The recent Isa Genzken show is a good example of some of that evening out. I mean how many women have had these huge retrospective shows there?

That was an amazing show. And there’s also the Lygia Clarke show, that’s wonderful. Yeah, I think things are changing, but slowly.

And then there’s this whole trend with these really highly priced very young men, with inflated prices at auctions.

But if you look at the work there’s no content in it, the work is a technique or a process. Someone said the work looks exactly the same in reproduction as it does in real life. And there’s something weird about that. So the work is made to be reproduced. The whole topic honestly gets me, I never know what to say about it, because I don’t want to just dismiss all young men as talentless, because I’m sure there are some that are really good, there always have been and there always will be, but there’s a lot of young women who are really good too.

But it’s not that young women should aspire to that necessarily, because I don’t think it’s good for artists to try to become that.

Right, I think it doesn’t matter the sex. When I graduated college, I had a full fifteen years if not more of nothing. Of just doing my work, developing, making tons of mistakes, making shitty work, making some good work, but nobody saw it, and I just think you need those years. You need to fuck up. You need to imitate your heroes and then you need to reject those heroes. And you need to try lots of different things and I think this brings us back to what’s being called Provisional Painting. I think a lot of that, especially from the much younger artists, it’s all trying stuff out. It’s just trying out things. And eventually if you work hard enough you’ll find your own way. But if you get a lot of attention for this kind of stuff that you’re just trying out you may never find your way because you’re blindsided by the other crap.

Joanne Greenbaum’s Tribeca studio.

So do you think there was less pressure for artists to make their work public before it was ready at that time versus now?

I don’t think there was less pressure, I think there were always artists that started showing when they were really young, I just think that economically there wasn’t as much opportunity, so there weren’t as many galleries as there are now and fewer artists in New York even though it was super cheap to live here. I think that when I was in school my teachers always said—and in a way we hated them for it—they all said don’t even think about showing—I mean you have 20 years! No one ever talked about the market with us. I know now there are classes on the marketplace. When I graduated from college and moved to New York I was starting my life and I knew it was going to be a long, hard slog. You got jobs and you cleaned houses and you waitressed and you did other things. I mean I ended up working for fifteen years in an office and had a responsible position and I liked it for a while just because it was allowing me to do my other stuff. Eventually things got confusing because I started to show my work and I couldn’t do both, I mean I really had to make a decision. I mean I guess nothing was handed to me—when I was a young artist I didn’t know about anything, I didn’t know what Skowhegan was. I didn’t apply to anything, I just went to a job everyday and I couldn’t take a month off and go to an artist residency, that wasn’t career path stuff in those days. Maybe it was for some people, but I didn’t even know about it. I was just a real head-in-the-sand kind of kid. I lived on the Lower East Side during the ‘80’s, and honestly I didn’t even know what was going on in terms of the East Village scene, I was so periphery to that. It just wasn’t my time. Sometimes you just instinctively know that this just isn’t your time, and even though I’m the age of a lot of people who were showing then, it wasn’t my time. And I just waited it all out and worked, and I worked on painting when people weren’t even looking at painting. And I just kept doing it because I really believed in what I was making, and then eventually I did start showing it. And honestly it’s still not easy, it’s tough out there.

Going back to when you were describing the forms in the paintings–are these images?

No, they’re not images, I mean the whole thing is an image, but no they don’t represent anything in particular. Everything functions for the painting, so whatever’s in it functions as it exists in the painting, it doesn’t really exist outside the painting. Obviously I’m interested in some sort of structure, and I think that the real subject matter of the painting is sort of my participation in making that painting. Kind of the slowness, even some of those things that look they were made fast, the paintings actually come together very slowly. I take my time. I might scribble something on it that’s fast, but getting to that scribble, I might have I lived with it first for a couple weeks or a few days. The accumulation of all of this stuff over a period of time is the subject matter of the painting in a way. There are formal decisions that go into it but in a way that’s what I mean when I said I have something in common with Josh Smith, I mean I think he’s really good at saying he’s just going to do whatever comes into his head and he’s not editing for good taste—there’s no editing whatsoever. When I start a work I make a point of starting from a totally empty slate where I don’t have any preconceived idea of what’s going to happen. Even if something is just a big disaster—that gets me all excited. Because then it’s just like, “oh okay, this is just a big disaster, I love it, good!” I don’t want to make something that makes sense. I’m not trying to make things that don’t make sense but I feel like I’m at a point now where I’m using that part of my brain that allows just something else to kind of be there and make the work. I’m certainly going for something, it’s just that I don’t necessarily know what it is until it happens. I want to keep the paintings open and I want to keep them fresh and I don’t want to make paintings that are resolved, so I’ll probably stop a painting before I even know what it is. Like this one, at some point I stopped it thinking I’ll get back to it when it dries, and then it dried and there wasn’t anything else I really want to do to it, so I guess it’s done. And sometimes the opposite happens—sometimes I’ll just hate it. Or sometimes I’ll turn it upside down and do one thing to it and then that’s it, that’s all it needed. So I try to keep myself kind of open to whatever’s going to happen. And I say that not referencing anything Abstract Expressionist, or gestural, or any of that. I don’t think about that stuff at all.

There are gestural qualities in the work.

Yeah, but I’m not interested in gestural abstraction as a thing. I’m using my hand and arm in making the painting. But I’m not interested in the historical aspect of what that gesture means—I think it’s been long enough to be able to use a gesture without it having to mean the ‘50’s or have it mean the New York School, that’s over. People in Germany were making gestural marks, Sigmar Polke made gesture. I think it’s time to give that up, just the way I think it’s time to give up that provisional mark making, it just doesn’t mean anything anymore.

So do you think there’s a lot of possibility left in abstract painting?

Sure, yeah. Because it’s just painting. I mean, I don’t see a difference right now, even though there’s no recognizable imagery in my paintings, I don’t really preference abstraction over figure. There’s no difference, it’s just all painting. I don’t privilege one over the other. People will still write novels, people will still make paintings. And I think it’s up to each individual to make it happen. Everyone’s different and everyone has something different to say. You just have to work really hard at it to get it to the point where you can say what you want to say. It doesn’t just happen on it’s own.

Besides being away from the studio and in a sculpture studio with a kiln, is there a difference in approach when you are beginning a painting from when you are beginning a ceramic work?

I go once a week at a specific time, because I take a class. And usually I make one or two sculptures for that session. I don’t carry the sculpture over to the next week, even though I’m told I should do that, but I don’t want to. I like making them in one session. I make it from a five or six hour time period that I’m there, and I’ll make one or two pieces during that time, and then that’s it, they’re done. There’s no going back, even though there could be, but I choose not to keep the clay wet for the following time, it’s just a decision I’ve made. I like the immediacy of the clay even though you could keep clay wet for a hundred years—you can keep clay wet a whole lot longer than you can keep oil paint wet. You can work on something forever and ever, but I choose not to. I just take clay and just start working and making stuff. I try to think of it as drawing almost, three-dimensional drawing, and as in the painting I don’t really know what it’s going to be, I don’t plan it out. It’s almost like I don’t care what I make, I just want it fired so I can paint it, either with glaze or paint. What I’ve been doing lately is—and you can see the one that I have here, this white porcelain—making them and then firing them and not glazing them at all, and then taking them back here to the studio and hand coloring them with markers or oil paint or ink. In a way it’s almost like they become kind of vessels for me to hand color or hand work or draw on.

Untitled, 2014, marker and glaze on porcelain, 13 x 8 x 7 in., Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery

It’s amazing how different these look, the glazes and the hand worked ones.

Sometimes I feel like glazing and sometimes I don’t. Lately in the studio I have a whole bunch going and some are glazed and some are going to have nothing on them and I’ll take them home and work on them. Like that purple one, that’s oil paint on porcelain. Porcelain is so beautiful, it’s high-fired, and there’s nothing on it, so the oil paint soaks into it and creates this beautiful kind of matte surface because the oil just disappears into the porcelain. So there’s a lot of potential—it’s just another way of making that I like. I know that a lot of people are doing stuff in clay now, which I think is great. What I’m not interested in is having one define the other. Yes, of course the painting and sculpture are related, but nothing is explaining each other. Somebody asked me recently why I didn’t show the sculpture alongside my paintings in my show, and I said I didn’t need to, I just wanted to show the paintings.

I think it was John Yau who was saying something about you no longer being a secret ceramicist.

Well, I’m not secret now but I was. I’ve started showing them now but before when I started I was secretive about it. I didn’t know what I was doing—I had never touched a piece of clay before so I needed to learn from the bottom up. I’m not presumptuous enough to think I was any good at it for kind of a long time. I was secretive about it just because I was learning and it was primitive, and also I think there was this thing where I was thinking “who am I to be making this sculpture now, like what is that about?”It just took me a while to process the fact that I was interested in something else. And also, it’s sounds so silly, but I was embarrassed in front of my sculptor friends. I wasn’t secret exactly, I just kept it quiet because I didn’t feel entitled to show it. And then in 2008 and 2009 I had a museum survey in Europe in two museums, and when the curators were here, I had the sculptures here too, and when they came to choose the work they saw the sculpture and they wanted to take them too. So I ended up having a couple rooms where there were paintings and a little installation of some of the sculpture, and it was great. But that was actually the first time that I showed it. And also the gallery that I used to show in that closed wasn’t interested in them.

Untitled, glazed porcelain, Courtesy the artist

I think it’s really interesting to have a practice that’s just for yourself.

Yeah, I think I started making it because I had a need to make them. It was something I was making for myself, and I still make some of these for myself. I also make stuff with this paper clay that self-hardens, and I paint them, I just have them on my painting table and whenever I have extra paint I just go over and paint on them. And that’s something that’s kind of a private thing.

Everything’s become so public now that it’s quite difficult to carve out a private space or practice that’s just for oneself that feeds or sustains you.

Right, but you can! You don’t have to show everybody or anybody everything you do. People do, but you don’t have to, you can hold things back. I think it’s okay to hold things back or keep things quiet, we’re sort of taught not to, everyone’s so self-promotional. I just think I don’t want to be like that.

Do you think that making the sculpture has changed your painting practice?

I think it did. I think the clay lends itself to a kind of fluidity and I think after a while those forms just ended up in the paintings. It wasn’t a conscious thing, it just happened, and with the clay there was something loosening up, and maybe I was struggling with that in my painting. I was somehow struggling with what I was painting and it needed something else and I think somehow instinctually I felt like I had to make sculpture, and then eventually it found it’s way back into the painting. And so I think that my paintings were much more geometric and hard-edged before, and now they’re kind of not.

You’re a developed, mature artist who has figured something about being a painter. What advice would you give on how to develop and sustain a painter’s voice throughout a lifetime?

I just think if you’re a real artist you will know it and you’ll keep working. I think if it means moving out of New York there’s nothing wrong with that. I think that unfortunately it’s just super expensive here now and why kill yourself to be just one of hundreds of thousands? You could go somewhere else where you could make your work without having to sacrifice your soul. I can’t generalize, because people want to be where everything is, but there are a lot of other places that are really cool besides New York. I mean if I was a young artist starting out, I don’t know if I would come here. I know lots of young artists who went to Europe, who went to Berlin, and other places. I just think the most important thing is to just figure out a way to make your work. My feeling is if you can just figure out a way to make your work, then you’ll be fine no matter where you are. If I had to do this over again now, I wouldn’t be able to do it here, because I don’t like living with other people, because I don’t want to have five roommates and share a studio. I didn’t have to do that–I had a little apartment on the Lower East Side and the living room was my studio and I slept in the little alcove room and it was great. But I don’t know how many people who can find their own apartments now for not so much money. I think because it’s a different world, meaning that because of the internet and globalization you don’t need to be here. You can go to New Orleans, or Detroit, or Berlin, or Dusseldorf, or Madrid, or Miami–there isn’t just one way to do things, or one path. You don’t have to do the whole grad school to cool gallery to being rich and famous. It doesn’t work that way because those people who have done that, when they’re 40, no one is going to care. You need to be in it for the rest of your life. Just be in it for the long term and don’t think of the short-term rewards and don’t go to graduate school and don’t have debt, that’s my feeling.