By ASHLEY GARRETT

Published in Figure/Ground April 11th, 2015

Brenda Goodman is a painter living and working in Pine Hill, New York. Born in 1943 in Detroit, Michigan, she attended the College for Creative Studies from 1961 to 1965. After a number of successful shows in Detroit, she moved to New York City in 1976 and was included in the 1979 Whitney Biennial. Since 1973 she has had 35 solo shows and her work has been included in over 200 group shows in galleries and museums throughout the United States, including Edward Thorp Gallery, Nielsen Gallery, John Davis Gallery and Pamela Auchincloss Gallery. Her work has been reviewed in many publications including the New York Times, Art in America, The New Yorker, the Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, the Brooklyn Rail and most recently in a review by John Yau for Hyperallergic. She received two New York Foundation for the Arts grants and the National Endowment of the Arts Fellowship. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Agnes Gund Collection, NY; the Carnegie Museum of Art, PA; the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, CA; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Detroit Institute of Arts; the Birmingham Museum of Art, AL; the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, MI; and the Elaine L. Jacob Gallery of Wayne State University, Detroit, MI. Recent exhibitions include “Another Look at Detroit” at Marlborough Chelsea/Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY in 2014, solo shows at John Davis Gallery in 2014, 2012, 2010 and 2008 and an upcoming retrospective at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit, Michigan in 2015. Her work is currently on view in her solo show, Brenda Goodman: New Work, at Life On Mars Gallery in Brooklyn, New York through April 19th and also in the American Academy of Arts and Letters Invitational Exhibition through April 12th, 2015. Goodman is the recipient of a 2015 Arts and Letters Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Brenda Goodman at the American Academy of Arts and Letters Invitational Exhibition with Stone Memories, 2014, oil on wood, 72 x 80 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Can you talk a little bit about the work in terms of the paintings that you’ve put together for this show, how you see it as a group?

I’ll tell you why these in particular, it’s because these are the only ones I have! I had a show at John Davis Gallery in July 2014 and in the fifteen minutes before the show opened, almost all of the sixteen paper pieces sold. Some of the people who bought them were old friends, some of them were new people, some of them were friends who had never bought my work before, and then the paintings started to sell, so by the end of that show there was one painting left and one paper piece.

Brenda Goodman: New Work installation view at Life On Mars Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, April 2015. Courtesy the artist and Life On Mars Gallery.

Wow, that’s great!

A little while after that, I think in the fall, Michael David offered me a show after looking at my website, which was wonderful and amazing. So I had that scheduled, and since I had nothing left in my studio, I started painting. I had to create a whole new body of work since September or October, and I did. I made nine paintings and ten 6 x 8 inch oil on paper pieces. Call me focused, call me very intensely focused! I was planning on three big ones for Michael and then the ones that were picked for the Academy were three big ones and so it was like – I’m just so sorry I’m having these problems!! So that’s why these particular paintings are on the wall, because these are the ones that I’ve done. Some people don’t believe I did them all in seven months.

Everyone does it differently.

Everyone does it differently, yes. I think one of the things that makes it go a little bit better then someone who hasn’t painted as long is that in 50 years I’ve learned a lot of things not to do. I’ve already gone through a lot of things that I know won’t work, although every painting has it’s little moments where you have to let go and give it over and surrender, but it’s not fraught the way it used to be. When you’ve painted a long time you get to know what mud is, and I know how to avoid it, stuff like that.

I started art school in Detroit in 1961, and that was for four years, since then I’ve had a serious studio practice. There were two times when I didn’t go in the studio for about 9 months. The first time was when I tried quitting a three-pack-a-day cigarette smoking habit, and there was no way I could be in my studio.

Why not?

Because the association of smoking and looking at paintings and working was huge! I was a chain smoker, so I had to not work until I was free of the feeling that I needed a cigarette, and then I was fine. And the other time was more recently when our 15-year-old dog died. Even though I’ve always painted my pain–if I have a signature it’s that– whatever I go through on some level, I paint. But when she died, I just couldn’t even do it. So I didn’t. And then I did go back.

I think it’s really interesting when you respect what your pain is asking for, or your process, and when something in you doesn’t want to work right then, that’s a thing that’s really interesting to listen to. Even when you think you should be working or doing and actually to just take the time off, it’s a risk.

You have to trust that. To do this amount of work in seven months is pretty amazing, and when I work I’m extremely focused and I get a lot accomplished, but when something’s going on, like when I quit smoking, I just cried a lot for all those months and released feelings that the cigarette smoking covered up. And the association was so strong to sitting and smoking and drinking coffee and looking at the painting, there was no way I could do it. So it was interesting when I went back to it and decided I wanted to do some free automatic writing just from my unconscious and a whole new series of wonderful abstractions happened, they were from 1985, I was showing with Ed Thorp at the time, I loved doing those. Something opened up, but I do trust the whole process. And more recently when my dog died – I still can’t talk about it, it’s still so hard. I couldn’t paint. But nine months later I finally did a painting where she was on a blanket after she died. It was one of my self portraits, it’s called Quandary and I’m looking out and I didn’t know where I was going to go with my work, what I was going to do but it was a beginning to enter the work again.

Quandary, 2011, oil on wood, 72 x 72 inches. Courtesy the artist.

We moved upstate five years ago, and that was a huge change to my work. My partner’s son died, and that was nine months from beginning to end, and it changed our lives as something like that does. We’d always come up during the summer and I’d paint in my studio, and then lug everything back to the Bowery with four flights of stairs, and then in June, we’d go back to Pine Hill and paint for the summer, and that’s what we did for a long time. But then when Jon died, we decided just to stay upstate. So we left everything in the loft, we only had what we would take for the summer, just my paints and some clothes, everything else wasn’t touched for a year in the loft, we never even went back. It was amazing how you can do with so little when you think you need so much and now it’s my full time studio! We settled into a life upstate and got my studio renovated and heated and insulated and now it’s my full time studio.

Although there’s more of a community for artists and painters up there now.

That may be, but I live in a pretty rural area. Although I have a couple painting pals and we share our work on a regular basis. My whole life I’ve been identified as a painter and it took a while when we moved up here to adjust to the fact that I’m just Brenda, and to let go of the other identity a little bit.

Two years ago – I’m bringing you right up to date – I weighed 185 pounds. I lost 70 pounds.

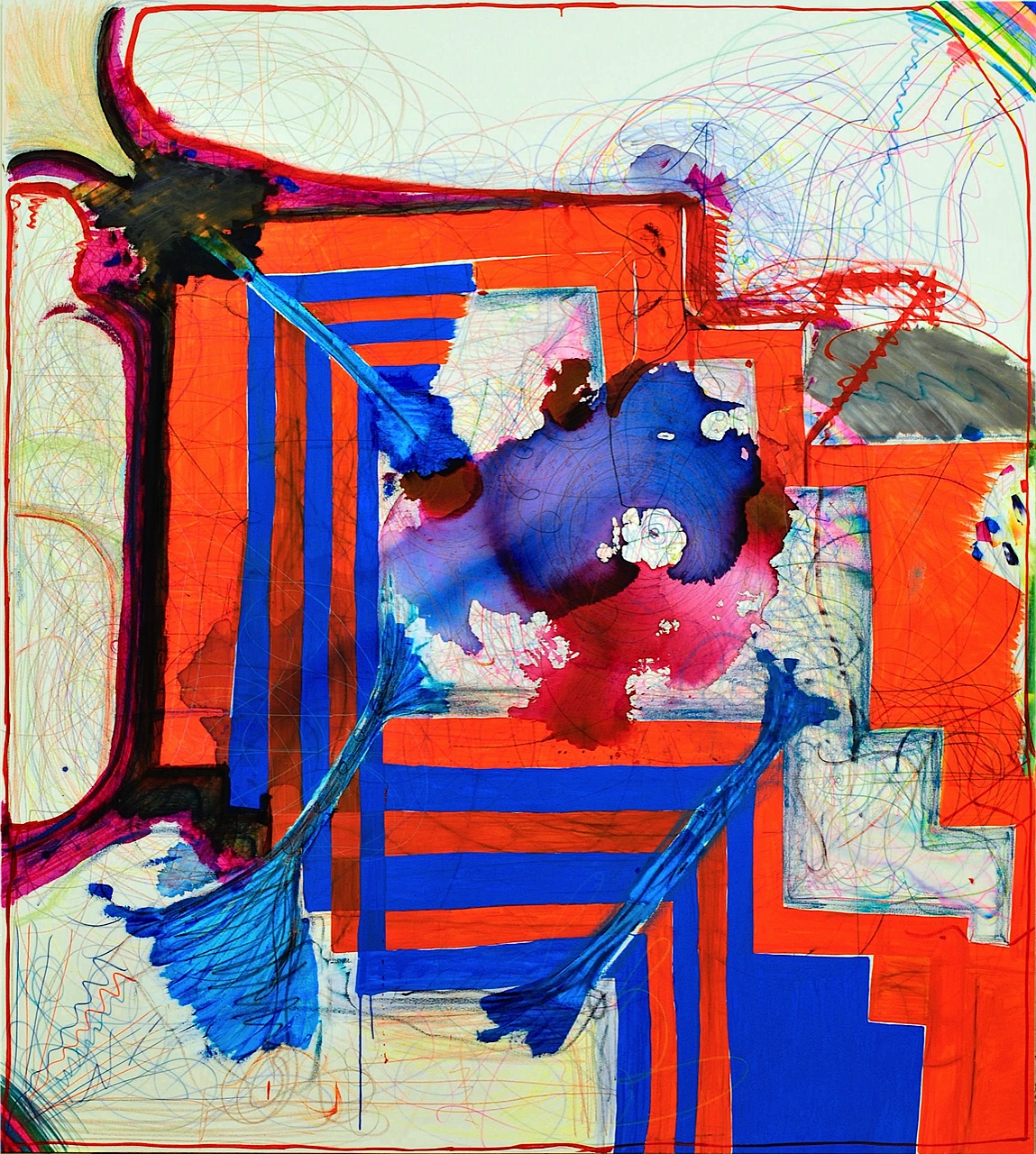

Soul Talk, 2014, oil on wood, 48 x 64 inches. Courtesy the artist.

So now having lost the weight, something happened, because this time I’ve kept the weight off for almost two years and I haven’t done that before, I’d always lose it and then put it right back on. It gave me a confidence internally, the confidence was always in my work, but not in me necessarily. I held back – I wasn’t animated, I wasn’t playful, I joke around and I’m lighter now than I ever was before in my life because something shifted, having dropped all that weight. And in the process the work shifted.

I was definitely going to say something about the palette shift in the paintings here…

The fine line between horror and humor is never going to go away in my work, because I spent my whole life on the dark side! But it’s definitely lightened up and it’s more animated to some extent. So when I started these paintings I just said each one’s going to be what it’s going to be, I never repeated myself over and over anyway in my work, and so every one of them is different, although you could look at some of these and see a connection to something that I did in the 70’s or when I was in school, it’s all so connected to me.

With the paper pieces, do you work on them at the same times as the paintings? Or are they a separate practice?

I’ve gotten into a kind of routine, I do a body of work and then just sit down and enjoy doing the small scale paper pieces. With the paintings I’m always standing and moving. But with the works on paper I set up a different palette. I did all of these works on paper for the Life On Mars show after the paintings were finished, so they were the last things for the show.

Sometimes my paper pieces don’t always connect to the paintings in the show, but in this particular show what pleases me is that the paper pieces really lock into the paintings. The paper pieces from my last show at John Davis had a whole variety of things going on, and in these they’re really more connected to the paintings, which really pleases me.

And they also look like they’re a little more abstract, so in each one you’re got a very particular kind of invention.

Soul Talk, 2014, oil on wood, 48 x 64 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Right, these are actually more abstract. Some of the ones at John Davis did have specific figures in them.

What was your first encounter with art? How did you know or discover that you were an artist?

I didn’t know when I was really young – it started in high school, I started drawing and then I started taking a drawing class at the Society of Arts and Crafts in Detroit, now called the College for Creative Studies. I did that for a little while in high school, and I got a scholarship to go there full time. I wasn’t even sure I was going to be a painter, I was doing sculpture, painting, and ceramics, and then it became clear that I was going to paint. So from ’61 to ’65 I went to school, and I taught there for a little bit. But I knew after that I knew if I didn’t quit I would probably still be there because that seems to happen to people. So I quit and I’ve been doing this for 50 years.

During your opening someone mentioned that the heavy black shapes in this painting (Soul Talk) are based on your early sculptures – that you were painting the sculptures into images. Is that something that you’ve done?

Those particular heads have come and gone for a long time in my work. When I first moved to New York, I had only lived in Detroit. I moved here and I didn’t do what I should have done which was to get a job and network right away, I sort of stayed by myself and there was a four year period where I felt pretty alone and isolated. I did some sculptures – they were sort of reflective of how I was feeling at the time. These beings that couldn’t really look out or look in. I used tar and feather on them, I still own one, but they were pretty intense.

What’s interesting is that certain things come back in the work, and it may not exist for ten years and then all of a sudden it pops back in and it feels so familiar, and then of course if I go back into my work, I say yes, I can see that connection. It’s because they mean something, and other times I use a shape that I’m just crazy about and resonate with and then I never see it again. And I find that so interesting! If you walk on the beach with someone, you might pick up certain stones you love and you resonate with, and the person you’re with picks up entirely different stones, why is that?

3 Sculptures, 1977, canvas strips, tar, string, wire mesh, approx. 67 x 12 x 11 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Something I really love about this work is that you seem very emotionally present in each one, I feel like you as a human being are putting yourself in a very vulnerable place with each one in a very particular way. I’m wondering if there was a decision on your part to put yourself out there in the painting or if that naturally developed?

That’s an excellent question because it does come up. I think there was only one time I felt some vulnerablility when I did a series self portraits from 1994. These self portraits – I still have one, no one can take it away from me. I could have sold it ten times by now. I’m learning, it’s still hard for me, to hold on to certain paintings for myself. Sometimes I’ve bought them back at auction and they’ve cost me five times more than what the person paid for, and I’m buying them so it doesn’t seem right!

When I did this series, I weighed 210 pounds. I had just come off of doing about ten years of the abstractions that I was talking about after I quit smoking, and it just wasn’t giving me what I wanted after a while. Abstraction for me is so loose and free and comes from another place but after a while it leaves that personal element out. So I wanted to deal with my weight, and I wanted to have something I could look on and reflect on where I was at. And these pieces certainly did do that! Then I did lose the weight, although I put it back on afterwards, but nevertheless, when I was showing these paintings, I was very heavy, but I didn’t feel as vulnerable as I did when I made the ones from 2003 to 2007. First of all they were more naturalistic, and I did four of these self portraits with a mask covering my head. Because I was so vulnerable and felt shame about my body but after four of these I took the covering off my head.

My mother was very critical of everything, she was not a warm and fuzzy mother. She would criticize everything I did but she also saved all the cards I sent her, so I got to see them after she died. There was one I found that I had written when I was fourteen years old, in it I said: “Maybe I’d be nicer and everything would be nicer if you didn’t criticize everything.” And what fourteen year old says that to their mother?! But when I saw that card it reminded me even back then that I’ve just always said what I felt. And sometimes I say way too much how I feel and I get in trouble. As David Brody said the catalogue essay, I wear my heart on my sleeve. I just say how I feel. And sometimes it’s very admirable because a lot of people don’t do that, or they fake it and they say things they don’t mean, and sometimes it puts me in the position of being too outspoken or demanding or whatever. But it’s who I am. And in my work I’ve always dealt with what was going on in my life. People say my paintings are so from the heart. I used to give intensives to people who had creative work blocks. And I was really good at intuiting people’s issues of what’s causing those blocks. And it’s usually that they won’t go to the dark side in their work. They’d rather paint nice.

Self Portrait 4, 2004, oil on wood, 64 x 60 inches. Courtesy the artist.

I like that expression, ‘paint nice’!

Paint nice – like getting praise, or nice colors, or it looks like something, it’s realistic, or something like that. I’d say – what’s the worst experience you’ve ever had? It often has to do with your mother for some reason, and I’ll say let’s paint that. And people will react: “I can’t paint that! That would be awful!” Like they would die if they painted what they felt. And I always said no, unless you can go there – you don’t have to stay there, like I have for so many years – but if you go there you can come back and paint how you want to paint, but it won’t be out of fear anymore.

I don’t get in front of a painting and think I’m going to be open or I’m going to be vulnerable or I’m going to be light or I’m going to be pretty or I’m going to be sad, it’s so who I am to the core. What I don’t like about work is when I look at it and there’s a wall between me and it. And that’s what happens when I do the intensives with people who have creative blocks, that wall is going to disappear the wall between the painter and the viewer. Everyone comes from a different place and there’s great things in the different ways people work. But I can always spot when someone has this wall. I strive in my work to have no wall between my painting and the person looking at it. You should want to be seen! I mean, what’s the point, what’s the wall for? Who are you? Be vulnerable! When people see my work it feels real to them, it’s not bullshit, it’s from the heart, there’s no barrier between me and them. When you meet me, who I am is what you get. I don’t have that kind of facade.

I’d love to talk a little bit about the mesh form in this painting (Almost A Bride) and how it developed. In this one it looks like its moving away from a kind of architectural structure and becoming more like a mesh or a screen, there’s an all-over quality to it, it seems closer in proximity to the picture plane and has all these wonderful variations in these kind of patchy forms.

The first one on which I started to use that kind of grid was in Soul Talk, it just sort of happened in that painting when I squeezed the paint out of a small squeeze bottle. I just started doing it and let it happen and I really really loved it. This was the first one where I really went crazy with the grid. I just really love it! And what it actually means, I don’t know. Sometimes, most of the time, I have no idea. All I know is when it works. And if something works, then I know it’s right!

Almost A Bride, 2015, oil on wood, 80 x 72 inches. Courtesy the artist.

In every one of these paintings I start by filling up the surface with marks and then I look at it and find some shapes, and then it just starts taking off and becoming it’s own life force. In this one (Moma…Please), the marks on the whole right side then became part of the finished painting. In some of them it’s completely hidden, you don’t see those original marks anymore. And in that one, there’s still some. So that’s the beginning point, and that’s why I think every one is so different, because the marks are different and then I interpret them differently in each painting.

In this painting (Stone Memories) there is the original gesture, and I put some washes over it and then it looked like a figure which seemed important. And then when the other shapes emerged, I knew it was a mother and child at that point. And that’s how it got the title “Stone Memories.” In a lot of my work I have an observer that’s watching and there’s a balancing act that’s going on–

And a pulling or resistance…

Yes, I like those dualities. In my last show I did a couple of small ones with the grid, and then I moved into these new paintings.

I thought Almost A Bride was finished in an earlier stage. It was more of a cross form, it had a figure, but a few people saw it and I got a ho-hum reaction. I usually pay attention to people’s reactions, if one person doesn’t like it and five people do, I’ll listen to it but I’ll go with what I feel. But for this one there were a few people who just didn’t respond well to it and then I looked at it and it I knew I hadn’t developed it enough. It was a cross but I knew it didn’t have the complexity I wanted. I felt like I could do more to it. So I went into Photoshop and I started experimenting with how to change it, Photoshop is very helpful to work out some ideas. And I decided to rework it. So I got rid of the arms of the cross…It got me mad that I didn’t see it myself! Because most of the time I see these things myself. But I changed it and I worked on it, and look what I got!

As far as the screen form goes–I wanted to emphasize it more, I wanted that form to be more dominant. And then all those formal decisions – my work is as much about emotion as it is about formal issues. (I have a very traditional background, my painting teacher wouldn’t let us use paint for the first six months, we had to use thumbnail sketches and then we had to use earth colors and then eventually we were allowed to use color.) I learned the fundamentals of painting inside and out and I still believe in them. And I always use deKooning as an example. You can be as free and emotional as you want but then you have to go in and light up your cigarette and make some formal decisions! Those clean, sharp lines, like in the women series, those were there to clarify the chaos around it, they were very intellectual, formal decisions.

Those paintings had both the emotional and the formal held really intensely together, you could feel the painting-mind at work and the thinking through but that didn’t cloud or distance that feeling of fear of women, the mother issues, those were all right at the surface.

That was the initial impulse, but then he sat back and said okay, there’s areas here where I have to make this a better painting, it can’t just be about this – although he would probably deny all those things you said–

It’s all over that work!

Yes, those are important things! And I think you see so much work now that lack depth and rigor. There’s not a lot revealed. No risk, no presence, just tossing one out after another, posting eight of them a day to social media, and getting the wows and going onto the next, and I hate that. It has to be more than that.

My life has been full of people who feel they receive something from my work. I did a series of empty room paintings in the ’80’s and they always had a little chair in it or a little something to say this is the story, and then there was one where it was completely empty with only a small shape and there was an opening and light coming in and onto the floor, it was very simple. And a friend of mine, who was dying of bone cancer bought that painting, she said that it gave her a place where she felt peaceful.

And I thought at that point that I could throw my brushes away! I’ve arrived at something important. And I guess I just feel that there’s so much work that’s just empty. There’s nothing there and there’s no risk, just ‘nice.’ And I think how long it took me in years to let go of a precious shape in a painting–you’ll relate to this, every artist will relate to this–you work around it and you work around it and you change this and you say to yourself – that area, I can’t let go of that area, it’s just so wonderful, everyone is going to love it, and I love it! And you go nowhere with this painting until you’re ready, and then you eventually have to give up that shape, and as soon as you give up that shape, guess what–

Haha, the painting gets a lot better!

The painting finishes itself in 10 minutes—and you feel like “oh, how did that happen? What’s all this called?” It’s called trust and surrender. And so, in the old days when I would have one of those areas it would sometimes take a week or a month to give it up because there’s so much will involved.

It takes a lot of artists even longer than that!

Yes, and then once you give up that area and it all falls in place, then you say: “oh, I wonder if I’ll do that again!” And it happens again and it stills takes a long time to give it up, and you’ll say to yourself, “it happened again!” And so fifty years later, when that happens to me, I know in a matter of minutes, maybe an hour, and then I know what I have to do. I think one of the most important processes of being an artist is how long it takes you to let go of your ego and surrender to the piece and trust that it’s going to be a better painting, and that’s huge. How long does it take you?

It depends on the painting.

How old are you?

I’m 30, about to be 31.

I’m 41 years older than you. So how long does it take you?

It depends on each one.

Well, approximately.

Each one is pretty different, but I’d say a week, two weeks, a month or so – it’s a whole range.

But you know the feeling.

Oh yeah, of course! It’s obnoxious. But it’s really interesting too because it also feels like the key to the painting. And so much of it is like, as you’re saying, dancing around resistance, but in paying attention to that you may end up with some other interesting things. It’s always in the back of the mind, knowing that you’ll have to go there eventually, but I’m not quite ready or I don’t feel like it, or I know it’s going to be a battle–

You can talk yourself out of it, it’s easy to do.

There was one painting that I did in ’85 that was in a show at Ed Thorp’s, and the whole painting was almost done, it was just one area that was not working and I was afraid to do anything to it, and yet I didn’t like it. I felt like I was in the darkest hell that one could possibly be in–the abyss was so dark and so deep and I didn’t think there would be light at the other end of it, although there always is, I didn’t think there would be light, and once I let it go it fell into place and that’s painting is called the Breakthrough–

It’s so educational, having those experiences, and they’re not all like that.

Of course not. That painting sort of painted itself. Some of these paintings don’t paint themselves.

Do you work with palette knives in addition to brushes? The textures of these paintings are so varied.

When I was a student I wanted to experiment with different textures and materials right from the beginning. And I would take all these notes on all these materials that I used to mix in the paint and through the years it’s just sort of become my specialty. I wanted to experiment with as many different tools and stuff to do my paintings because I feel that the more ways you can handle the paint with as many tools as possible you have more ways to communicate your feelings. I also want people to think they’re as wonderful close up as they are far away. Sometimes if you only know how to use wash brushes and make pretty skies and you want to make a dark intense something-or-other, how are you going to do it? You have to stop your practice and go learn a new technique, which might take a day or it might take two years. I don’t want to do that, so I learn all these things as I go along.

There was a series of big triptychs I did in 2002 that have a lot of washes—I was watching television and happened to see a program about home and gardening, there was a woman on a ladder with one of those foam rollers and she was painting bamboo leaves. So the next time I went to the hardware store, I got a couple of those. And all of a sudden all this new stuff started to happen in the work, like I was able to put a warm and a cool wash wet in wet in a whole different way. So over the years I’ve built up techniques and tools, for those thick marks I have cake decorators with different tips and I have squeegies and I have foam brushes and I have foam rollers and I have Q-tips and I have palette knives—I just use whatever I feel I need to use. Also I mix pumice and ashes from our wood stove into some of the surfaces. I use whatever I think is going to work emotionally—like for these grid forms/screens, I squeezed the black out of a small plastic bottle.

I can really tell!

But I knew it was going to create a certain feeling, so I had to do it. And contrast is extremely important to me too. Busy, active, surface variation–all those formal things, thin, and thick. When I was a student I would paint one side of a wall with sand and the other I would glaze, and yet visually it held together, and that was a real challenge. And I still think about things like that—how many different things can I do and still make it visually work and create the feeling that I want? So materials and tools have always been a really important part of my process, I spend a lot of time preparing my studio setup. I have really thin white oil paint, I have thicker white paint, so it’s all ready to use as I need for a particular painting.

Is there a risk of taking the emotional/feeling part of making these painting too far and into a kind of therapy? Is it about changing how you feel or is it about working through or resolving it or is it something else?

Good question. No one’s ever accused me of using my work as therapy.

It came up in one of your other interviews from 2010, the one with David Brody for Artcritical. You were talking about this painting (Self Portrait 16, 2005), and he said: “It’s refreshing to hear an artist so committed to the painting process and the materials of painting talk about a therapeutic value to art…” So I was wondering about that, do you feel like when you’ve worked on something that it’s solved therapeutically for you?

It’s happened a couple of times. Sometimes early on some people said I was using art as a cathartic thing, because it was right on the edge. There’s only been two times when my painting changed something in me. I wish it was more often but I guess that’s not bad in terms of one’s work.

One was when my mother died on my birthday when I was 29 and she was 52. When I turned 52 I got really angry at her because I was afraid I was going to get everything she had, because those are what genes do. I started to do a series of paintings that I thought were going to be very angry and ugly, and all of a sudden I was using all these bright colors and I had no idea where all of that was coming from! And my mother loved color and I didn’t. I was using a lot of praying figures at the time and I was also anchoring in a combination of the abstract and the figurative. So I started using all these colors and I thought, “this isn’t right, these are supposed to be dark and ugly!” And then I realized that when I was doing them that the color was for my mother. Something released in me, and the series became “Songs for My Mother” instead of “You Bitch,” or whatever else. I never felt that particular anger or resentment or fear of her illnesses again. It released me of feeling all of that.

And then the second time was that painting, Self Portrait 16—she was not a warm, affectionate mother. Her own mother died when she was five years old, she was raised by her sisters, I never touched anyone or hugged anyone either, and I was just like her. She got lung cancer and when she was dying in bed in the hospital, I didn’t even know to be able to sit down next to her and hold her hand. So that little character at the end of the bed, that yellow one, was me watching her. She had an oxygen thing over her and she died. And it was in this series in 2005 where I finally dealt with that, I wanted to paint that. And recreate it and see if I could heal it. So I painted that painting and put myself next to her bed and held her hand. With the other character still there just watching, but it healed something in me. I couldn’t do it while she was alive.

Self Portrait 16, 2005, oil on wood, 48 x 40 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Wow. That’s what is so magical about painting, it can change personal history.

Those two paintings changed me. It brings tears to my eyes even now, because it did do that. I watched people who were able to hold their parents while they were dying, I just couldn’t do that.

But you did get to. Thank you for sharing that, I think that’s amazing. I also think it s a kind of testament to how many people really respond to your work because you’re very direct about that. These are feelings everyone has at some time in their lives–everybody has a mother, everybody suffers, everyone’s parents die at some point—I think it’s a really special thing when you’re able to communicate that to yourself and other people.

Absolutely. People feel it. That’s basically what I do, and it’s also an accumulation of painting for fifty years. When people get frustrated when they’re younger, and they can’t do it, they just haven’t lived long enough yet! The paintings will fill up and develop if you let them, you have to have that whole mixture come into you that you can put in the work. Losing your mother is the biggest thing, you don’t get over it ever. You internalize it and hopefully something comes out that’s meaningful that other people can get something from.

I really enjoyed your essay on the Painters on Paintings blog about Guston, and I’m so sorry to bring up Guston but I can’t help myself…

Go ahead, bring him up!

I know this has come up for you in other situations, the whole question of influence and you probably get really tired of hearing that all the time, but I feel like you’ve integrated him and addressed all of that head-on…

I didn’t always, Ashley. Sometimes, in the 80’s if someone said I see Guston in the work, I would get defensive and say “well if I was older and he was younger you’d say his work is like Goodman!” And I was defensive because I knew he was an artist I resonated with. It wasn’t like he had something and I was taking what he had, I had that in me too. After a while I decided to let go of being defensive so now when someone says they see Guston I just say thank you. I was also Dubuffet for three years when I was a student, every time I picked up a pencil I was Dubuffet. I’m someone who believes in influences and yet sometimes I was wondering where I am in all of that. And I remember my teacher saying “walk like him, talk like him, paint like him, be him” and I started to do that and it finally got out of my system and as long as I was fighting it or fearful of it or reacting to it, it didn’t go away.

That’s the interesting part for me, that you’re not fighting it or trying to get rid of it anymore, you haven’t made Guston into a painting nemesis. You’ve accepted him and moved through him.

Yes, because I think my work has moved on. There was a time when it was more of an issue. I had a lot of telephone anxiety at one time in my life and I did a series of black telephones on a table and a couple of years later I see a book of Guston still lifes and he had a painting of a telephone called “Anxiety.” An identical black telephone! And in a bigger way no one can use red, black, gray and white and not have someone say Guston. I don’t care if you’re doing a photographic vase with flowers, someone will say they see Guston in it. When I quit smoking and I wanted to paint myself with a cigarette, someone came in and said well Guston had—you know the one where he has the cigarette hanging out of his mouth. And I was like “well I’m so sorry, I’ll never do that again!” The work has changed, in the one that was in that “Guston Curse” article, Not A Leg to Stand On, there is a recalling of Guston, but in a very different way, it doesn’t look like a Guston. But it’s always going to be there, as will some of Dubuffet, some of Gorky, some of deKooning and even Morandi who I love more than even Guston, is part of the artists that I carry with me. In Not A Leg To Stand On, after that painting was done I said “Well here we are, me and Mom.” She was so big and I felt like I never had a leg to stand on. She was stretched across the whole thing and then there was this little figure with this head and it had one yellow leg and I said “oh shit, there I am without a leg to stand on.” And I was so excited that I wasn’t even upset, that the painting revealed that to me, I love when that happens, I wish it happened more but when it does it’s just so fulfilling.

It’s great to have some kind of externalized forms for all these massive feelings that can take over and be too heavy. It takes some of the pressure off.

We’re lucky that we have this, I mean, what do you do if you don’t have this?

What advice would you give to a young artist just starting out?

Learn your craft. Experiment as much as you can, try as many ways of working as you can. Let yourself be influenced by as many artists as you can. Take risks, paint mud, paint beauty, paint life, paint death. Paint your best every day in your studio. Don’t compromise to others and don’t compromise within yourself. And always follow your heart and let it take you where you need to go.