By ASHLEY GARRETT

Published in Figure/Ground Nov. 28th, 2014.

Ann Craven lives and works between Manhattan and the banks of the Saint Georges River in Maine. With a particular perspective on nature as her subject, Craven’s most recent show that opened at Hannah Hoffman in Los Angeles last weekend brings forward Craven’s point of view of rural nature vs. urban color. In the studio, Craven uses both digital and direct observation as sources for her Moons, Birds and Flower paintings. She recently had her first retrospective, titled Time, at Le Confort Moderne in Poitiers, France this past summer. Other recent solo exhibitions include Maccarone, New York, and Southard Reid, London. Her work has been exhibited internationally and reviewed in publications including Art in America, the New York Times, Artforum, Flash Art, The New Yorker, Frieze and Modern Painters. Her paintings are in the public collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum, the New Museum, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, among others. Craven is represented by KARMA, New York.

Ann Craven in her New York studio, November 2012. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio.

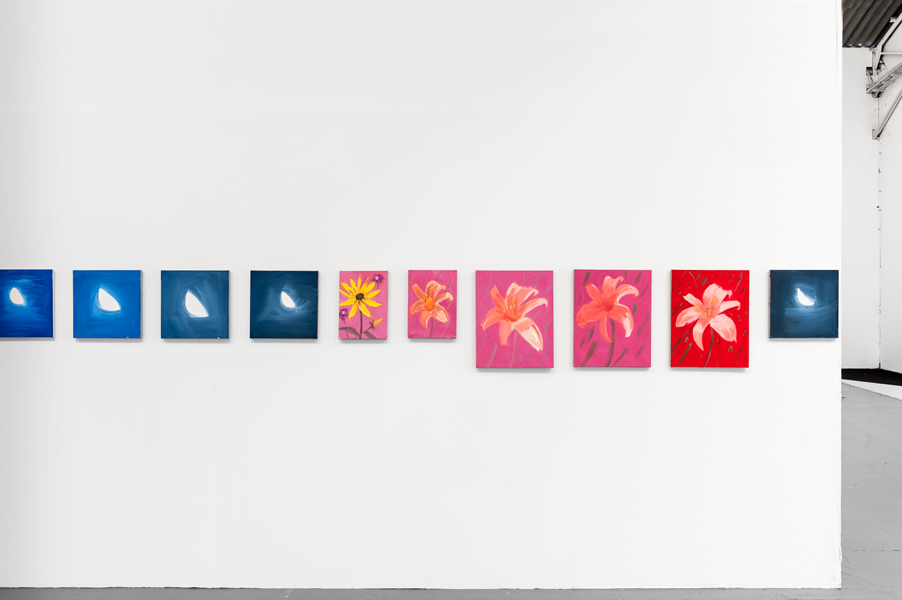

When we first spoke on the phone you mentioned the group show you were in that was organized by Retrospective Gallery in Hudson and curated by Erin Falls – the Ambulance Blues show at Basilica Hudson. That show closed mid-August, so I missed seeing it in person, but I did find nice installation pictures online, so I was able to look at those and read a little bit about Erin Falls’ idea behind the show. You mentioned the installation of your moon paintings was a little different for this show – I was really curious about that, knowing how you have shown the time-based moon paintings in a large array. Here you showed only blue moons rather than black moons, and it looks like the blue moons are more of a shortened sequence rather than a long group of the phases of the moon. This feels more like a deliberate sequence. Did you choose this particular sequence of moon images for this show? They all look relatively full. How do you see your work relative to Falls’ conception of the show?

Ambulance Blues installation view at Retrospective Gallery at Bascilica Hudson, New York, August 2014. Courtesy Retrospective Gallery.

It’s interesting that you’re saying that they look as though they are sequential because that group of paintings were painted in two evenings in 2012. I think we gave them to her in the 2012 series, actually from two nights in June of 2012, so I painted one after the other after the other, and I had four or five easels set up. Where I am in Maine you have to catch the moon at a certain time and it’s spectacular! It’s like watching the most amazing performance that’s on this Earth, the moon rising. You have to be ready for it. All the canvases are primed and ready to go in order, and I just grab them and put them on the easel, usually at least two easels going at once if not four, and sometimes I’ll finish one and twenty minutes later I’ll finish the next one, and twenty minutes or an hour later I’ll finish the next one. My titles are the times the paintings were made. Each work describes the exact time I stopped painting, so it’s “Moon (Place, Time), Year.” It’s a system, so the hanging can also be a system.

For that show, the paintings were hung like one long sequential thought. One continuation, but with fragmentation. Erin placed this work within this incredibly heartfelt show – I think the fragmentation of the evening was something so poetic and how occasionally you look up and see the moon if you’re not painting it – most people don’t paint it – but it’s just a documentation of time so it’s a different fragment of different parts of an evening, or a day or a month or a year. So they were hung higher than usual. We discussed that because the space was so huge and high that we decided to hang the paintings a little higher so that people would have to look up instead of just being given the paintings. They’d have to look up as though it was the moon in a physical form.

I was wondering about the title of the show – it made me think of the Neil Young song of the same title, although there was no direct reference to it in the press release, but then in listening to the song again, reading the lyrics and a little bit about it, it totally fits the work. It’s a nine-minute song from the album “On the Beach.” In it there’s storytelling, both personal and cultural trauma, and sequencing, but also how trauma can instigate and develop change on a really fundamental level. I’m just reading the lyrics – and I thought it related to your work in an interesting way:

“I guess I’ll call it sickness gone

It’s hard to say the meaning of this song

An ambulance can only go so fast

It’s easy to get buried in the past

When you try to make a good thing last”

So I was thinking about the way you work, and the repetition of your paintings, and it’s a really nice dovetail into the way you’ve built up these images many, many times. What is the relationship between the past and present for you?

People are being conceived under this moon, people are being born under this moon, people are dying, living, crying – so for me, the moon – I don’t often talk about the emotional side, because it does become a system for me too, I hide in the system. The size is always the same, like a song, a repeated mantra so it’s also like a prayer.

When I say a song I mean I can always revisit it again but it always sounds a little different. It’s something that I know will be there for me always, that I can revisit, and that it will always be both different and the same. I started painting the moon a long time ago and I was very embarrassed about it. I come from an Irish Catholic family in Boston that believed in me so much as a painter. When I told them I wanted to be an architect in college, they were like “Why? You’re a painter! What about the smell of oil paint?” I love my parents so much, I’m so thankful they said that, because what I’m doing now is because of them.

Moon (Cushing, 7-21-13, 11:05 PM), 2013, oil on linen, 72 x 72 inches. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio and Maccarone, New York.

What was your first encounter with painting? How did you become an artist?

I started painting with oils when I was six. Believe it or not, I was given a set of oil paints and canvases and canvases to finish, because my aunt had passed away and my mom naively let me use them. She let me use oil paint and I had to use turpentine, but I had to be but careful enough that it wasn’t a bad toxic experience. It wasn’t like she made me be – oh no, you can’t do that, she was more like, oh yes, you can do that! And not only that, she put me in an art class with adults, so I got to learn how to paint at night with these very intelligent older women who would give me hot chocolate and they would be drinking coffee. I learned about oil painting. I’ve never used acrylic in my life, oil is in my blood, I know it so well. I’ve been painting for a long time, so the subject matter came later but the process was always something that I understood and was almost kind of embarrassed about because I knew so much about oil painting as a kid and into college. I never took it for granted but it was just always there, that I know so much about this material – now what do I do with it. What do you do with it? And that’s a question for every artist, I think.

Exactly. The subject matter has to come out of the paint itself.

Yes! It has to come out of the paint, that’s exactly right. Especially wet on wet – oil paint is so much easier for me than thinking about waiting for layers to dry. It’s so immediate.

Your work is very rich in the handling, the brushstrokes, and the color. You’re working with imagery that might seem sentimental, such as the deer and flowers and birds. You were also saying that you’re interested in systems, and the titling is always important in reading any work, in terms of classifying how to look at it – at what point do these become conceptual paintings? How much is conceptual and how much is it painting because you love painting, using images that might make you vulnerable or taking risks? Are these conceptual paintings? Or are they a balance between conceptual and something else?

Great question. The painting process for me is deep, it’s my blood, so it’s always going to be something that’s so emotional.

It’s so interesting that you asked this question because I really feel that when I fell in love with the work of Agnes Martin, it was because I understood her scheme, a beautiful scheme to kind of turn her back to the world, and be like get out, get away from me, this is my time and my hand going across this canvas. So I really related to that way of thinking. And at the same time, making sense of the lists, I love to make lists and I need lists, I’m a constant obsessive list-maker– my lists are an archival project as well, to archive my body and where I am. The way that I title the moon paintings has everything to do with where I was at that certain moment, and a sequential timing of my presence in this world. In a way it’s a documentation of the fact that I was here.

Poppy (Early June, Cushing, 7-2-13), 2013, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio and Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers.

I think that the conceptual part of my work is going to always be this sort of list-making, and the more emotional will always be the paint, it’s my blood, it’s my heart, it’s my soul, I can’t deny that. So, when I title my work and put it in front of me, I see it also as though it were a diary, because it shows the timeline.

When you’re doing the observational painting, like the moon, and you then repeat those paintings, what is it that you learn in that exchange of information, what is the change that happens between observational experience in the painting, and then repeating the image that’s already been painted, is there anything that you acquire or learn or let go of in terms of your experience in the paint, or information in the image?

That’s really interesting, in a way for me it’s like how a poet revisits a poem, and then wants to change a certain word or a comma or a fluctuation in a sentence or something but then doesn’t. In a way I feel really lucky to be able to revisit something again and again and again, being each time that it’s different – it’s a different time, it’s a different place, it’s a different motion, it’s usually an attempt at all the same colors, although it’s always a different mixture but it’s very similar, and I want always to have that availability to go back and revisit and re-mix a certain color. But – everybody does this! I really feel that every artist, and everybody who is practicing things in terms of form, I feel that people revisit their ideas, you revisit your notions.

I paint from life, like the moon, but each painting is done on the same 14 x 14 inch canvas, so I do have a system there – I have rules that I can break within the surface of the canvas. But by repainting my Puff Puff series of bird paintings, that I revisited many times because it was an interesting subject, I changed the background color, I changed many things in that one series.

Ann Craven: Time at Le Confort Moderne, Pointiers, France, 2014, installation view. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio and Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers.

When you’re painting the moon – is it different painting from observation versus painting these pre-established, kind of sweet images of the deer and birds, the found or culled images? What is your attraction to painting those images at the same time as the moon, which has a sort of totemic symbolic quality? How does that relate to the deer and the birds and flowers? I’m referring to the figure/ground relationship between seeing things “in the round” versus flat photographs.

I love to print out images that I like from the internet.I constantly find postcards and I go to postcard shows all over the country when I can find them. It’s one of my favorite pastimes, postcard shows — you’ve got to go sometime, it’s incredible! For me, those images hold so much value for my inspiration.They are flat because they’re reproductions, but they’re reproductions that are sort of off key. I like vintage postcards of birds, because the print quality is off, it’s wonky, it’s not going to be perfect, and I value that. And so I have thousands of images that I save – weekly, monthly, yearly – and I’ll take those images with me in suitcases, I have certain images that I need with me as inspiration that I lay out on the floor. A lot of the flowers from the series of bird paintings that I’ve done have been painted at one time from observation. And I then mediate it myself by printing them out.

It’s like one feeds the other. I grew up painting from observation, and so I learned how to paint in the round, I learned how to paint looking at the glass and seeing the water, seeing the light going through it in three ways, and painting that. And the awe of being able to paint that – I always want that, I need that in my work, and so they both go hand in hand. They have relationships on both ends, all the time.

Dear and Daises (Life of the Fawn), 2004, oil on canvas, 72 x 108 inches. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio and Maccarone, New York.

I was thinking about the repetition and how you were repeating whole shows after years have gone by – repeating series of paintings many times. And then I read that you had a studio fire in 1999, and I was wondering if there was a connection between that and the impulse to repeat your work. Is the subject or purpose of your work to document and preserve memory itself? Is this work about time travel or the refusal to acknowledge the passage of time in the face of terrible loss? Did the fire push you towards wanting to reacquire memory in a different way?

That’s pretty profound stuff you’re saying – do you have like a week or so? Let’s hang out! Then we can really talk and talk!

I hide from the mere fact that somebody might see that and see through it and see through all this repeated stuff to see that I’m acknowledging the passage of time. I’m looking it in the eye and trying to actually come to terms with death and life at the same time. And not go too close to admitting it – you can’t say it, because you don’t know what everything’s like after or before, and if you can grasp it right now in front of you then that’s being in the moment and being in the moment is so scary. Or stillness, quiet, silence, there’s frightful things in silence as well, so I like to think that my work is memory or that I can paint something and I can always revisit that and I don’t have to remember it, I can always remember it if I need to go back to it. The fire was definitely an eye-opener wake-up call to the fact that I am coveting my work again, in the event that this does happen again at least I have another one! But I was making copies before the fire.

As a matter of fact, at the time I was working on a huge series of deer paintings, and one was at a gallery. After the fire everything was gone but one deer painting, titled “Deer and Daises,” which was returned back to me about two months before my first come-back show in 2002. The fire was in 1999, and I was just devastated for a few years. But that deer painting – I repainted that deer painting and had to show it in the show. Then two years later I repainted that whole show and tripled the size of the paintings and hung the paintings in the same place and space. It was again a re-claiming of time and also a passage of time, in itself being that “hello, wake up,” to myself, to the fact that I’d shrunk myself as well, because everything was bigger, the brushstrokes were bigger, all the work was magnified.

I think most human beings are profoundly afraid of change, because as you said, it brings forward the fear of death. I think your work invites a conceptual reading, but also because of the way it’s painted, the feeling with which they’re painted, it’s hard to not see that other side. So I actually don’t think it’s quite as hidden under the conceptual guise. But I do think you’re inviting multiple readings, although you’re touching a very particular nerve of humanity: I don’t want things to change, I want them to stay the same. Stability is so important for human beings.

I grew up in a family from day one where it was always about us not being here — “You know, we’re not always going to be here,” kind of thing, and so it’s in my psyche to always try and hold on to the ‘what’s here.’ The heartfelt stuff is something that I’m almost – you can only show it so much, but as a learning experience for myself, and as a sort of protection element for myself, it’s all of these learned ways to hold on, and give up, and let go at the same time. And it’s so interesting; it does come out of suffering.

Ann Craven, installation view at Klemens Gasser + Tanja Grunnert, New York, 2002. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio.

Ann Craven, installation view at Klemens Gasser + Tanja Grunnert, New York, 2004. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio.

You’ve said that your stripe paintings are coming from your palettes or are your palettes. Why do you make the colors into stripes? What is your interest in transforming them into that particular form?

My palettes are pretty much as close to my gut as you’re going to get, because that’s where everything happens. And it’s something that as I’ve learned as a child, this constant mixing, and making color –what’s a color? And I really understand mixing. I come from a roofing family, so there was a lot of process going on there, and covering – I learned a lot of continuum stuff from my grandfather who had to do the same thing a lot. But the mixing of the palette came from the way that my grandfather would do this black mixing of the tar.

I use small stretched canvases as my palettes because they hold up better. I get these really cheap canvases and put them on my studio table.And I keep the palettes because I always need to revisit the paint, to mix the color again in two years or a year or less. So there again, it’s a list, it’s documentation. My palettes have always been a list. It’s always interesting for me to see my palettes, to see how many I have – I have hundreds of them. For the stripes, I was taking the paint from the palette and making it a line. And making the next color a line, and the next color a line, and the next color a line. So that I could see what I just painted, actually see it, instead of mixed up into the painting. I had just painted flowers or the moon or deer, I had a palette in front of me and the paint came off and went straight onto another canvas, so I could see the color. The mixing of the palette is a very unconscious process and so the stripes will always remain that too. It’s hard – I just want to paint stripes sometimes, and that’s it! Or nothing on the canvas, I’m so jealous of people who do that. So in a way the stripes are the closest I’ve come to of my realization of Agnes Martin’s realization of form and time, so the stripes are pretty potent.

They feel like a nice foil, where they’re related – they look like the same hand when seen together, but maybe not separately. They look like you’re taking a breath from the imagery.

That’s interesting, because it is the last thing I do when I’m working, and I think, “I can make my stripes now.” They’re bands of color, so they’re band paintings.

Stripe Triptych (Black, Blue, Purple; Orange, Blue, Brown, 2-01-08; Green, Yellow, Purple, 1-31-08), 2008, oil on canvas, 60 x 148 inches. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio and Maccarone, New York.

That makes a difference in terms of the art historical reference of stripes, where you might end up in the same territory as Daniel Buren with the authority of the stripes. But these don’t look like they’re charting that territory at all.

Exactly, I hear that sometimes from people, because Daniel Buren’s practice was definitely about stripes and about that sort of repeated image, but my stripes which I now call bands, are different because they’re born of the palette, it’s much more about giving birth to the color, or letting it free, rather than containing and going a different route. It’s a totally different process than Daniel Buren sort of gender-oriented work that he did. So this is non-gender, but they are very much about more of a birthing and coming from something else and something so private.

Ann Craven at Maccarone Gallery, New York, 2013, installation view. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio and Maccarone, New York.

Speaking of abstraction and figuration, because there seems to be and probably will always be, this over-arching conversation about progression in painting, or the death of painting, I’m wondering what your take is on the possibilities in painting in the future or in the present, because it’s always being talked about – what’s allowed in terms of image or in description and detail, in figuration or abstraction. You’re making these very particular figurative paintings and at the same moment painting these other works that feel related but also different, it’s something that might be seen as abstract although you might not see it as abstract, so I’m interested in your take on the future of painting, or the present of painting – what do you think are the possibilities for painting?

Well it’s such a great question Ashley, because you know, sometimes I get really insecure about the idea that it’s just paint, and what am I doing? Why would you be doing this now? And I turned a deaf ear to all that stuff about painting being dead but I always found it so fascinating, the discussion of how that essay has resonated through so many different passages of painting. And it’s really allowed painting to lean on when it was sort of a real statement of death. It’s a very hard question, I think people have to be – and I say this to my students too – if you’re there for any kind of market reasons, painting is something that has to be your life and your blood and you have to live and breathe it and if you’re doing it for any other reason then you have to stop, don’t do it, do something else. I think it all comes out in the wash at the end, you see through things. I mean obviously you believe in painting!

I do, it’s no secret.

Haha! You obviously believe painting is alive and it’s still right here. You’re proof of it.

I think it’s as alive as any of us will allow it to be. Because there are still people my age, younger than me, and older than me, who believe that – and there are – then it will always be around.

Left: Flowers installation view at Maccarone Gallery, New York, 2010. Right: Roses (Black and White Fade), 2010, oil on linen, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy Ann Craven Studio and Maccarone, New York.

I don’t think it could ever go away. Sometimes I hear on the radio about the idea of something being handmade, and it’s relationship to the digital age now and the screen, and I always laugh because painting is so universally ageless, it can’t possibly go away, because the handmade will always astonish and freak people out, because you have the guts to make something!

Marie Howe, the poet laureate of New York, was talking about homemade food, how that can strike people really intensely – like wow, homemade food! With McDonalds being around and still attracting people but homemade food is always going to be very special.

And the most deeply nourishing thing you could eat, assuming it’s well-made and it’s good, the actual homemade meal, made by whoever it is, with that level of consideration and care, then it feels like the most nourishing item you could put in your body. Like the physical expression of love.

Yeah – exactly! And it will always shock you that somebody made this amazing thing from hand, in the same way as painting.

I saw your work this summer in a group painting show at Zach Feuer – two of your bird paintings alongside some young artists. And I think you also showed at Essex Flowers recently – because you’ve been showing alongside young artists and in artist-run galleries, I’m curious how you see the dialogue developing between established artists such as yourself and young artists. What do you think established and emerging artists are sharing with each other? Why are you interested in participating in that dialogue?

I love that question! It’s so funny because the majority of these shows that I’m in are because of my former students who are now either running an artist-run gallery or curating an interesting project online. I just find it fascinating to be surrounded by these young thinkers who I worked with lot before they were making their more mature work. Heather Guertin was my assistant for four years and we’ve talked about so many things, and she’s a complete artist from head to toe, but she’s also really caring about what other people in her community are doing. So is Joshua Smith who works with her at Essex Flowers. And Heather is a very clear thinker and in addition to her painting practice she also does performance, which is for me both entertaining and shocking and great, but her paintings are fabulous. Heather doesn’t need to perform, but she does, and I love it! And then at Zach Feuer, one of the curators for that show, Jesse Greenberg, was my student at Columbia. He’s great, he’s running his own gallery, churning new things through painting – and there we go again, painting! But it’s coming out differently. That to me is the painting that’s not going to die, that whole show was Jesse and MacGregor Harp’s thoughts on their own work. They’re coming in the back door, it’s very interesting.

And at the same time they are part of the establishment, because I think some of them are doing art fairs this year, and even last year – but I think that’s really interesting because they’re claiming territory that’s both inside and outside the system, which I think is actually a new idea from plain old rejection or just trying to accommodate what the system already is.

Exactly! I really feel the same way. The art fairs were so poo-pooed by so many of the older artists, like the “I’ll never go to an art fair” kind of thing, and these young artists are embracing that whole system and using it to their best advantage. I love it, it’s fascinating to me to see this.

And speaking of this – what advice would you give to younger artists? Young painters in particular – how to sustain their voice? What would you say to a young painter starting out who is trying to figure out how to be an artist?

I think that as an artist, one knows that there’s a higher sense to what you’re doing and there’s a way to climb in – you either come in through the skylight or you come in through the front door or the back door. You need to get inside the house, or the place where you want to be in terms of your own work. The house is usually a safe place, but if you forget your keys you’ve still got to get inside. So you’re home, you’re inside, but you need to feel that you’re allowed to be someone who’s an artist and not have to hide it. I’m talking about myself in a way because I’m still shy about being an artist – how do you justify it? But there are a lot of young artists who are vulnerable enough to know that it’s not easy, so my advice is if you think it’s easy, then you have to be careful, because you need to be aware that it’s not too fun. But you should try to have fun, and stay true to your soul and yourself, because I think the soul is there, it sticks around, so you should want to make it something that’s physically available to yourself and vulnerable enough to yourself, but also that you know it’s something that’s going to stay if you want it to. By telling your story so many times you can make people believe it whether it’s true or not. The fake story will always come out eventually, but if it’s a real story and you really want it heard, it will get out there.