By ASHLEY GARRETT

Published in Figure/Ground Jan. 27th, 2014.

Lori Ellison was a nationally exhibiting artist and writer living in Brooklyn, New York. She received her BFA from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1981 and her MFA from Tyler School of Art in 1996. She attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1993. Ellison worked with notebook paper and pen in addition to gouache on panels, and she has also worked with egg tempera, enamels, and glitter. Ellison was also a poet and aphorist. Recent group exhibitions include The Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, CA, Philip Slein Gallery in St Louis, MO, and the UB Art Gallery at SUNY Buffalo. Her work has been reviewed in The New York Times, New York Magazine, Artcritical, Hyperallergic, and numerous other publications. Ellison’s drawings are in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Her paintings and drawings are now on view in a solo exhibition entitled “Lori Ellison” at McKenzie Fine Art in New York through February 16th, 2014.

I first encountered Lori Ellison’s work and writings on Facebook. Special thanks to painter Ben Pritchard for introducing me to Ellison during Ellison’s opening reception at McKenzie Fine Art on January 10th, 2014. Thanks also to Brian Wood for his help in the development of the interview questions and to Valerie McKenzie of McKenzie Fine Art in New York for her help with this project.

Can you talk a little about your background and upbringing? How did you become an artist? What is your first memory of acknowledging/discovering art and finding your place in it?

I drew all the time when I was a child and the womenfolk in my family said I would be an artist when I grew up and I tended to believe them. I grew up in the DC area so my parents took us constantly to the museums there so I had a lot of early exposure to art.

When the time came in my senior year to apply for college, my father and I decided going into commercial art would be practical and so I applied to Virginia Commonwealth University and got in to the Communication Arts and Design department. What I learned about design I use intuitively with the work I do in abstraction.

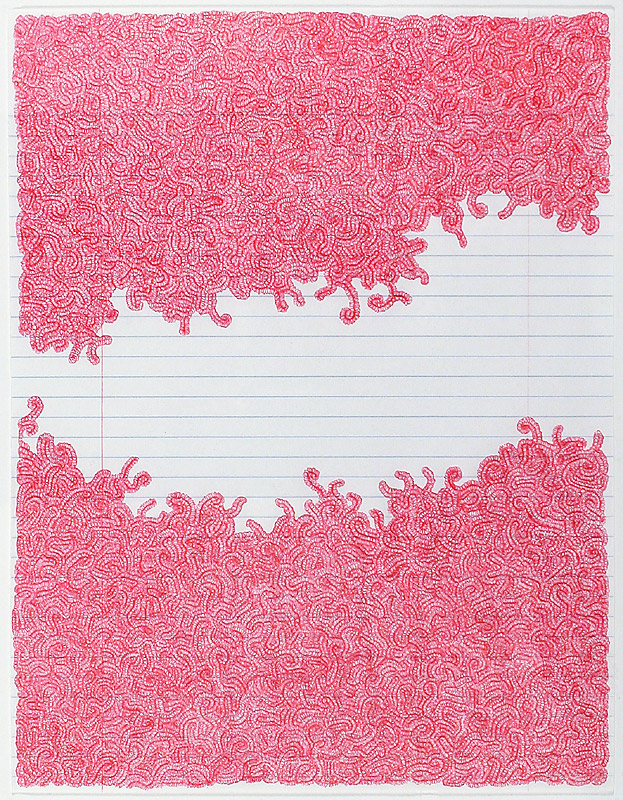

Untitled, 2013, ink on notebook paper, 11 x 8.5 in., courtesy the artist and McKenzie Fine Art, New York

What effect did moving to New York City have on your work?

The first summer I was here, in 1996, (right after graduating from my MFA at Tyler School of Art) I was subletting a space without a studio or an air conditioner. I had discovered myself doodling motifs from my paintings in my notebook during lectures and artist’s talks. I had a college ruled notebook and started making serious drawings with a Papermate ballpoint pen in cafes and diners for the air conditioning. I took my work to Pierogi and met so many artists in the neighborhood of Williamsburg, and some collectors and artists bought my work.

Kasia’s was a Polish restaurant I went to frequently for lunch and coffee and an artist named Greg Stone pointed me out to art critic Sarah Schmerler and she wrote an article called “Working in Brooklyn” for Art on Paper Magazine including my work and four others who worked in what has often been termed an obsessive style. Due to this article my work was purchased by the Rothschild Foundation for a works on paper sweep donated to the Museum of Modern Art.

New York was hard on me in the early years though, I was getting hourly wage jobs that didn’t last very long and my art was selling for very low prices. Through sheer determination I kept making my work on weekends and in the morning before I went to work and was included in group shows here and there, enough to keep my hopes up.

The turning point was in 2008 when I had a two-person show at Sideshow Gallery in Williamsburg and Jerry Saltz and Roberta Smith came and both wrote about me for New York Magazine and the New York Times respectively.

Why do you choose to make your drawings on notebook paper? There is a shared public history with most everyone understanding the meaning of lined paper—as doodles or notes or related in some way to language, a shared intimacy of writing, both public and private. Do you see the materials as a bridge between your visual work and your writing and aphorisms?

I started with notebook paper and have resisted change. I like the blue lines showing and everyone can relate to doodling in a notebook while stuck in classes all those years of schooling. I write poems and aphorisms and think of them as quite separate from my drawing and painting life. I did do a series of ballpoint pen drawings of my aphorisms with a goth girl lettering I came up with and combined the two that once.

Untitled, 2013, ink on notebook paper, 11 x 8.5 in., courtesy the artist and McKenzie Fine Art, New York

A lot has been said by you and others about the concept of scale and the effect it has on the making of your work. Can you talk a little bit more about your attraction to what you’ve called the humble scale and how you discovered that a smaller intimate scale is right for your work?

To best answer this, I will share an essay I wrote on humility and making small work:

In Richmond, Virginia there once was a gallery named RAW for Richmond Artists Workshop that had an exhibition of many works entitled “Small Art Goes directly to the Brain.”

If one is lucky, Small Art goes directly to the heart. For this it must be humble and on a suitably modest scale – in this way some work can be crowned Great. (Golda Meir once said “don’t be humble, you aren’t that great.”) To work with humility, one must acquire some of the practical virtues artists need: diligence, temperance, modesty, bravery, ardor, devotion and economy.

To work with humility it is better to strive for the communal if not the downright tribal; for wisdom in choices rather than cleverness; good humor in practice; and practice as daily habit. Phillip Guston famously said he went to work in his studio every single day because what if he didn’t and “that day the angel came”? Henry James once said, “We work in the dark, we give what we have, our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task.” Doubt is humility after a long, long apprenticeship.

Small works dance a clumsy tango with one’s shadow. Huge works can ice skate over one’s nerves, file under fingernails on a chalkboard – I can just hear the screeching.

If our work is so small and reticent that one doesn’t enter the space of the painting, no mind – we just might be making work that enters straight into the viewer’s ribs. I am weary of art that tickles my forehead for an instant and is gone – I am looking for the kind that thrums in my chest and lodges there, in memory, like those souvenir phials of the air of Paris Duchamp proposed.

Proportion based on the lyric, not the epic – that is where the juice lives. Stirred, not shaken. Duchamp once said that art is the electricity that goes between the metal pole of the work of art and the viewer, and I don’t need shock treatment. Art that is the size and resonance of a haiku, quiet and solid as the ground beneath one’s feet – not art that wears a monocle and boxing gloves in hopes of knocking other art out of the room. A discrete art, valiantly purified of the whole hotchpotch of artist’s tricks and tics.

Untitled, 2012, gouache on wood panel, 12 x 9 in., courtesy the artist and McKenzie Fine Art, New York

That, that is what I am looking for.

In looking at and reading about your work, I don’t feel it’s about repetition or obsession or even meditation (as understood in the more casual sense of reverie) at all. To my eye it is an extreme, razor-sharp precision of seeing, of knowing another space physically and deeply, a little like in your poem Tondo of a Goose Chase: “selfdeaf and selfblind.” Can you talk a little bit about your process? Do you work and write in tandem or does one feed the other?

First, I would like to thank you for not finding my work obsessive. This has been the knee jerk reaction to it for many years now. Recently James Kalm posted his video of my show on Facebook and called my work obsessive. Two people defended my work saying it was not obsessive. I was grateful to both of them.

My process varies from drawing to drawing or painting to painting – sometimes I work from the center outwards, sometimes from the edges inwards, and sometimes up and down or left to right.

I write from one area of my mind and make visual art from another area of my mind. I have never come up with what to write while working on a drawing or painting. They are quite separate operations.

Untitled, 2012, gouache on wood panel, 12 x 9 in., courtesy the artist and McKenzie Fine Art, New York

You’ve used Facebook a great deal as a way to both create dialogue with others and to share writings about your work as well as your poetry and aphorisms. When did you join Facebook and what effect did that have on your work? How do you see the development of the social network and communicating about your work and dialogue the way you do as an important part of your practice? What kind of dialogue are you looking for?

I joined Facebook in 2010 after making a drawing entitled “Facetime Not Facebook.” I was resisting before I joined up but liked it right away when I did join. It has been very important to me – the first time I came out as a poet. (I had never told anyone in the art world that I also wrote poetry.) I had not written many aphorisms since my original burst of over 100 in the year 2000 but found Facebook a perfect platform for them. I only post my artwork, my aphorisms, my poems and share political things on my newsfeed normally. No updates of microchanges in my emotional temperature or chat about the weather. My husband says I have a cult following on Facebook.

I came across your work in that same way—by noticing the conversation that other artists were having with you when you said “Formalism is not without content.” It’s very interesting, because a lot of people jump in to just agree with you, or show their own biases or thought processes, and then it breaks open when someone asks what the word ‘formalism’ means in the first place. I think it was George Rodart who was trying to pin down a definition and said that no one knows what it really means. What is formalism to you and what is the content that emerges from it?

I went to Wikipedia because though I know what formalism is through practice and discussion, I couldn’t form it into a brief definition. Here is the first paragraph:

In art history, formalism is the study of art by analyzing and comparing form and style—the way objects are made and their purely visual aspects. In painting formalism emphasizes compositional elements such as color, line, shape and texture rather than iconography or the historical and social context. At its extreme, formalism in art history posits that everything necessary to comprehending a work of art is contained within the work of art. The context for the work, including the reason for its creation, the historical background, and the life of the artist, is considered to be of secondary importance.

Untitled, 2013, ink on notebook paper, 11 x 8.5 in., courtesy the artist and McKenzie Fine Art, New York

I often write aphorisms and poetry over my head so to speak, although I do know what they mean, I share them to see what others make of them. I find myself resisting explaining them unless it has come across unclear in a specifically addressable way.

I loved this aphorism of yours:

“I love works that are so simple yet no one has done before. There is a sense of recognition as if the idea had been waiting for the right artist.”

It made me wonder what your take on postmodernism is? Can you talk a little bit about making art that’s of your own voice in this particular moment, one of prevalent postmodern ironic art? As you said recently on FB—Formalism ends where postmodernism begins. What did you mean by that?

Postmodernism was something we read about in graduate school, although our instructors were mainly abstract artists and chose not to speak in that language. Kierkegaard said “Earnestness is acquired originality” and I hold on to that in making and looking at work that I respect. Irony is needed in life, especially when one is younger, but it doesn’t need to go into the work.

I had to explain the aphorism Formalism ends where postmodernism begins: I mean in individual practice formalism ends when one starts making things from a postmodern point of view. Several people thought I meant it historically whereas I meant it in an individual’s practice. It led to a good discussion on Facebook. It came out of the discussion started when I posted Formalism is not without content.